|

Technically,

domestic cats belong to the class Mammalia (mammals), the order Carnivora

(meat-eaters), the family Felidae (cats), the genus Felis (lesser cats),

and the species cattus (domestic cats): that's our cat, Felis cattus.

There are three genera of the family Felidae: Panthera, the large or

greater cats; Acinonyx, the cheetahs; and Felis, the small or lesser cats.

A fourth genus, Smilodon, the saber-toothed tigers, just missed by only

12,000 years: almost no time at all, geologically speaking. Technically,

domestic cats belong to the class Mammalia (mammals), the order Carnivora

(meat-eaters), the family Felidae (cats), the genus Felis (lesser cats),

and the species cattus (domestic cats): that's our cat, Felis cattus.

There are three genera of the family Felidae: Panthera, the large or

greater cats; Acinonyx, the cheetahs; and Felis, the small or lesser cats.

A fourth genus, Smilodon, the saber-toothed tigers, just missed by only

12,000 years: almost no time at all, geologically speaking.

Since there is

of necessity a lot of discussion about cat sizes using the terms "large"

and "small," we shall use the terms "greater" and "lesser" in reference to

the genera. The terms "greater cats" and "lesser cats" refer to size only

in general: the larger lesser cats are larger than the smaller greater

cats. The most obvious difference between the two genera is that greater

cats can roar and the lesser cats cannot. The ability to roar is

determined by the structure of the throat: most significantly, the small

bones (the hyoid bones) that support the larynx. In the greater cats,

these bones have been partially replaced by cartilage, allowing

extraordinary flexibility of the throat and enabling the cat to roar. In

the lesser cats, these bones are rigid and roaring is impossible. Contrast

the deep-throated, deafening roar of a lion to the snarling cough of a

puma.

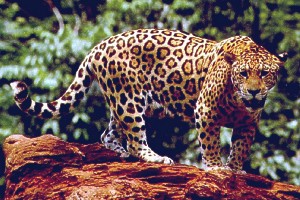

The genera are divided into species. Generally speaking, two dissimilar animals belonging to the same genus are considered as belonging to different species if they do not interbreed and produce viable offspring: they either physically cannot interbreed, such as a puma and a

housecat (boggles the mind, not to mention the housecat!); would not

interbreed naturally, such as a jaguar and a leopard, which just don't

have the right smells and signals to inspire mating; or their offspring

would be sterile, such as a lion and a tiger, whose offspring is a "liger"

if the father is a lion or a "tigon" if he is a tiger, but is always

sterile. Conversely, if two such animals do interbreed and produce viable

offspring, they naturally and quickly become the same species even if they

weren't to start with -- interbreeding will do that sort of thing --

though they may maintain enough differences to be classed as separate

subspecies.

There are some notable exceptions to this rule, particularly

where man has interfered. The species Geoffroy's cat, for example, can

physically mate with the domestic cat and produce viable offspring, but

would not normally do so in the wild, as the smells and signals are wrong

and the mating instinct would not be triggered. Man has successfully

circumvented this, however, and produced viable offspring in a attempt to

produce cats with wildcat patterns. Such hybrid off spring are usually

treated as a subspecies of one species or the other, based upon dominant

characteristics: so far, only new subspecies of Geoffroy's cat have been

produced, not new domestic cats. This is not the case with other hybrids,

most notably the Bengal is a domestic cat-leopard cat hybrid. Differing

species come about through isolation. If some members of a species become

separated from the main body of their species by distance or natural

obstruction, they will eventually evolve into a different species, losing

the ability to interbreed.

All members of the genus felis, subgenus felis,

have a somewhat complex relationship to each other. The parent species in

this group is Felis sylvestris, the European wildcat, who first evolved

some 600,000 years or so ago in central Europe (where he can still be

found). During the Second Ice Age, he extended his domain into Africa and

Asia. As the ice receded the seas rose and the climates changed, the

immigrant species became isolated from each other by water, deserts, and

mountains. Over time, the isolated subspecies evolved into the Sand Cat,

the African Wildcat, the Forest Cat, the Black-Footed Cat, and the Chinese

Desert Cat: other species also evolved, but failed to survive. Species are

themselves further divided into subspecies (if wild) or breeds (if

domesticated): the two classifications are analogous to each other. We

should remember that Panthera leo azandica (the Congo Lion) has exactly

the same relationship to Panthera leo that Siamese Cat has to Felis cattus. All members of the genus felis, subgenus felis,

have a somewhat complex relationship to each other. The parent species in

this group is Felis sylvestris, the European wildcat, who first evolved

some 600,000 years or so ago in central Europe (where he can still be

found). During the Second Ice Age, he extended his domain into Africa and

Asia. As the ice receded the seas rose and the climates changed, the

immigrant species became isolated from each other by water, deserts, and

mountains. Over time, the isolated subspecies evolved into the Sand Cat,

the African Wildcat, the Forest Cat, the Black-Footed Cat, and the Chinese

Desert Cat: other species also evolved, but failed to survive. Species are

themselves further divided into subspecies (if wild) or breeds (if

domesticated): the two classifications are analogous to each other. We

should remember that Panthera leo azandica (the Congo Lion) has exactly

the same relationship to Panthera leo that Siamese Cat has to Felis cattus.

Don't be fooled by the Latin: if a zoologist set up a "zoo" of domestic

cats, he'd find a Latin or Greek word for "Siamese," tack it on the end of

"Felis cattus," and call it a subspecies. It would still be a breed. All

felids, regardless of genus or species, have certain basic things in

common.

In appearance, they all look like cats. While this may be arguable

in the case of the Jaguarundi and, to a lesser degree, the Flat-Headed

Cat, it is definitely not true of some other families: all members of the

canid (dog) family, for example, do not look like dogs (not even all dogs

look like dogs!). Besides a similarity of appearance, all cats have

retractable claws: even the cheetah, the most primitive of all modern

cats, has partially-retractable claws. The most cat-unique common

characteristic, however, is purring: all cats, and nothing but cats, purr.

For some time it was believed that the greater cats didn't purr: some

texts still say this even today. This is patently not true, all cats purr:

lions purr, tigers purr, cheetahs purr, leopards purr, jaguars purr, pumas

purr, bobcats purr, domestic cats purr; all cats purr, without exception.

This alone proves common ancestry: probably Pseudailurus, 28 million years

ago, or Dinictis, 40 million years ago, depending upon whether saber-toothed tigers purred, something our own Neanderthal and Cro-Magnon

ancestors failed to note.

There are also a whole slew of internal

similarities, as would be expected. Besides the biological similarities

among cats, which one would expect, there is one other distinguishing

characteristics. Wherever it has adapted, in whatever ecological niche in

whatever part of the world, the cat reigns supreme among carnivores in its

size class. It is the penultimate hunter, with a finely-honed stalking and

killing ability that other carnivores can only dream about. The typical

member of family Felidae scores in 30 percent of its hunts: no other

carnivore, including man, comes close. It is also a merciful hunter,

killing quickly and cleanly by severing the spinal column of its prey and

minimizing the pain and suffering.

Some zoologists break the three genera

down further into subgenera based upon subtle or newly-discovered

differences. As an example, the subgenus Leopardus, the South American

lesser cats, have 36 chromosomes instead of the usual 38, (probably

through a fusion of two chromosomal pairs). This is a major distinction,

even though it is invisible to the eye and depended upon modern technology

for its discovery, and is usually considered a legitimate subgenus. The

subgenus Lynx, on the other hand, is based upon the lynx and its relatives

having short tails and tufted ears, a more obvious but also more trifling

distinction. The subgenus of a wild species is given in brackets in the

species list, and would replace the genus in nomenclature: "Felis [Puma]

concolor" may be "Puma concolor" instead of "Felis concolor," but never "Felis

puma concolor." The relationships between subgenera can be clearly seen in

the family chart. Some zoologists break the three genera

down further into subgenera based upon subtle or newly-discovered

differences. As an example, the subgenus Leopardus, the South American

lesser cats, have 36 chromosomes instead of the usual 38, (probably

through a fusion of two chromosomal pairs). This is a major distinction,

even though it is invisible to the eye and depended upon modern technology

for its discovery, and is usually considered a legitimate subgenus. The

subgenus Lynx, on the other hand, is based upon the lynx and its relatives

having short tails and tufted ears, a more obvious but also more trifling

distinction. The subgenus of a wild species is given in brackets in the

species list, and would replace the genus in nomenclature: "Felis [Puma]

concolor" may be "Puma concolor" instead of "Felis concolor," but never "Felis

puma concolor." The relationships between subgenera can be clearly seen in

the family chart.

All species of cats have differing subspecies (breeds),

not just the domestic cat. There are, for example, nine subspecies of

lions: Panthera leo azandica: Congo Lion Panthera leo bleyenberghi:

Bleyenbergh's Lion Panthera leo hollisteri: Hollister's Lion Panthera leo

massaicus: Massai Lion Panthera leo persica: Persian Lion Panthera leo

roosevelti: Roosevelt's Lion Panthera leo senegalensis: Senegal Lion

Panthera leo somaliensis: Somalian Lion Panthera leo verneyi: Verney's

Lion The difference in lion subspecies reflects variations in size, color,

territory, etc., with the names coming from the discoverer, classifier or

territory.

The number of recognized subspecies of a wild cat species will

be given, but individual subspecies will not be named. One small footnote:

don't let the "scientific" name of the various cats fool you. Zoologists

are as silly as the rest of us when it comes to naming things, but they

hide their silliness behind a Latin or Greek facade. As an example, the

scientific name for the common stripped skunk, mephitis mephitis,

translates to "smelliest of the smelly." In our own case, the Latin word "felis,"

generic for "cat," is derived from the older Latin word "felix," meaning

"happy," probably because cats are not shy about letting the world know

when they are happy, which is most of the time: they purr (purring also

makes the cat owner feel happy).

This means that "felis cattus" could be

translated as "happy cat" or "purring cat," and the family "Felidae" means

"one of those who are happy." Deep stuff here! In order to be fair, and to

give the zoologists their due, the Romans did call just any old cat "cattus,"

and one of their cats "felix cattus." (No, "felix cattus" does not mean

"Felix the Cat," though we can see where Otto Messmer may have gotten the

name.) The Species of Cat All in all, there are 38 recognized species of

cats: six greater cats, panthera; one cheetah, acinonyx; and 31 lesser

cats, felis, including the domestic cat.

All of them except the domestic

cat (and even some of those) have one thing in common: they are wild carnivores and will often bite and scratch when encountered (bigger ones may

also eat!). Count your fingers after petting! A description of each of the

38 species is given. Considerable thought went into the order in which the

species should be listed. Most lists give the greater cats, then the

cheetah, then the lesser cats, with the order within each genus being

either the alphabetical order of their English or Latin names or the

territory in which they were first discovered. None of this seemed to make

sense here, so we decided to list them by weight and size, largest to

smallest. Alter nate English names are given after the primary name, and

subgenera are given in brackets.

The weights and lengths shown are for

average male specimens of the various subspecies of each species: females

tend to be slightly smaller. Please remember that new subspecies, or even

new species (see the Iriomote cat), may be discovered at any time. When

taking the domestic cat as a species we intentionally chose to use the

typical feral cat a a model -- one that has returned to the wild state.

Because of random interbreeding among feral domestic breeds, the dominance

of certain genes, and the non-survival characteristic of certain traits,

there has come to be established a definite and distinctive species: the

medium sized brown or red mackerel tabby shorthair.

When discussing the

subspecies (breeds) of the domestic cat taken as a species, it is

important to remember that several new breeds are created each year,

several breeds are discontinued each year, and there is no agreement among

"experts" as to what defines a new breed, making the exact number of

breeds impossible to compute. As an example of this disagreement, a blue

(gray) British Shorthair is usually classed as a separate breed, the

British Blue, but a black British Shorthair is not. Overall, there is a

definite upward trend in the number of cat flavors.

|